How the Eiffel Tower was sold for scrap

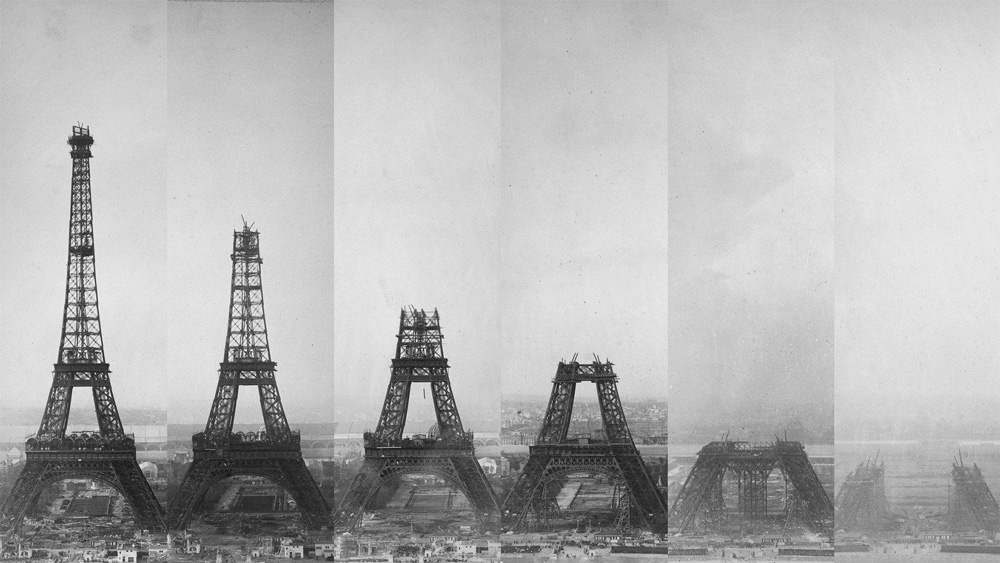

The group of businessmen was gathered in the Hôtel de Crillon, a luxury hotel in the centre of Paris. They had been invited there by the Director General of the French Ministry for Telecommunications, who stood before them putting forward an extraordinary proposal. He explained that the Eiffel Tower, erected almost 40 years earlier, was a burden on the state. The cost of its upkeep – the painting, the repairs – was exorbitant. In addition, on an aesthetic point, the style of the tower wasn’t in-keeping with the rest of the city’s Gothic architecture. The Eiffel Tower has been built for the World’s Fair in 1889 and was never intended to be a permanent fixture of the Paris skyline. It was time for it to go.

Shocking, perhaps, but it shouldn’t have blindsided the audience entirely. There had been murmurings of this kind for a time, articles in the press recently had called for the tower to be dismantled exactly as this official was discreetly suggesting. Removing this architectural blemish made sense – and why shouldn’t they profit from it? They were all in the business of scrap metal and they were being offered 7,300 tons (7,300,000 kg) of iron that could be melted down and resold. The successful bidder would own the structure and was sure to make a lot of money.

As the meeting drew to a close, the men were asked to keep the project confidential. The Eiffel Tower, in spite of its problems, had its supporters who would be sure to cause a fuss were details to leak. Assured of their discretion, the businessmen left to consider their offers.

One of the men in attendance that day, André Poisson, was particularly keen. Younger and less well-established than the others, he knew that securing the rights to the tower would put him firmly among the big players. He met again with the official the next day, just the two of them this time, to talk in greater detail about the purchase. The government official, a small, well-dressed man in his mid-thirties, was able to reassure him on certain points. The deal became all the more alluring. In the course of the meeting, Poisson also learned that the ministerial man wasn’t the upstanding citizen he at first appeared. He complained about his salary – code, Poisson knew – to say that he was willing to take a cash bribe to award the contract favourably.

Poisson talked the matter over with his wife. She urged caution but, for Poisson, this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. It was too good to miss. Putting any reservations to one side, he paid a large bribe. And waited.

It’s nearly 100 years since André Poisson bought the Eiffel Tower, planning to demolish it and sell it on for scrap. At the time of writing, the Eiffel Tower remains resolutely in place: tall and magnificent, a glittering beacon in the City of Light. So what went wrong?

Poisson waited to hear from his ministerial contact but was met with silence. The bitter truth soon became apparent: it was a con. There was no sale, that was not a government official. The business cards he had handed out, the ministry stationery on which the invitaitons had been issued, were forgeries. Horrified and humiliated, Poisson chose not to report the matter to the police. He preferred giving up any hope of recovering the money to being a laughing stock.

At the same time in Austria, Victor Lustig was keeping a close eye on the French press for any mention of the Eiffel Tower’s supposed sale. Every day for several weeks he scanned and discarded newspapers finding no mention of the search for a fake ministerial official. His gamble on Poisson had paid off. Lustig could read people – you had to in his line of work – and was confident that Poisson would be too embarrassed to report that he had been scammed. Just as Lustig had known that Poisson’s insecurity made him the most vulnerable to fall for his con, he had been confident that his fragile ego would silence him in the aftermath. Assured that he had evaded justice, Victor Lustig did something that was either utterly foolish or brave: he returned to Paris to pull the exact same con again.

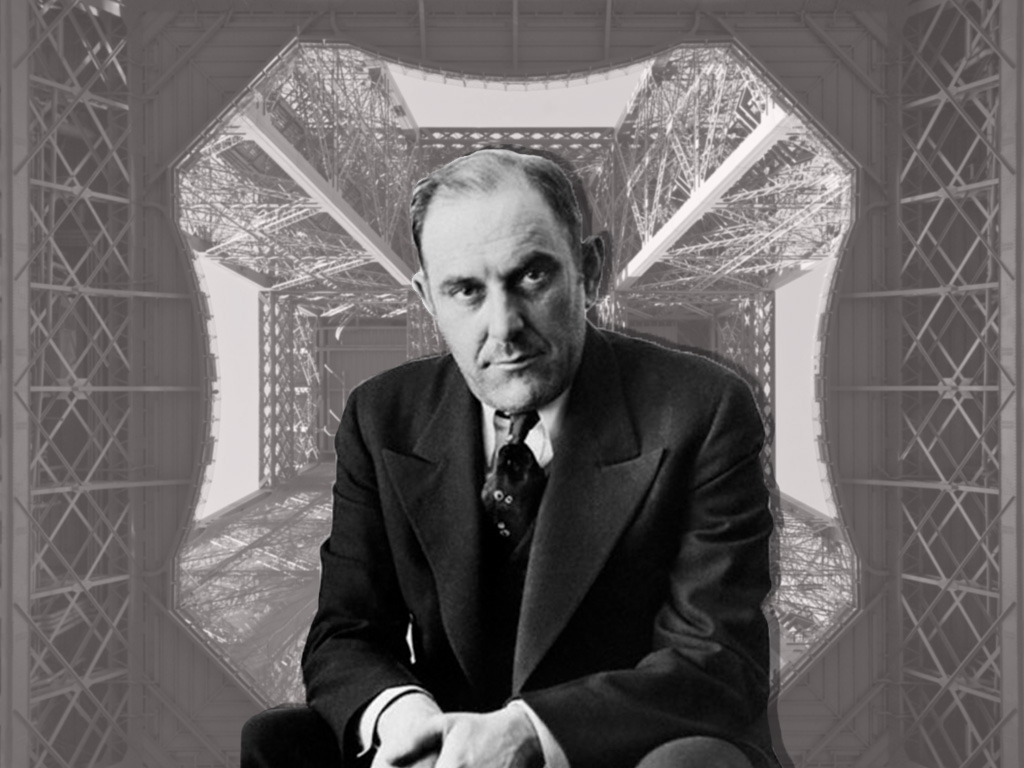

Like much about Lustig’s life, his time and place of birth are hard to acertain, as is his real name. What is believed, more or less, is that he had a humble start to life in 1890 in a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire that is now the Czech Republic. He was exceptionally bright and excelled in languages (he was fluent in five) but was regularly in trouble. After leaving school, he made his living scamming people, often on transatlantic liners, convincing rich passengers to invest in Broadway shows that would never be produced. When World War I put an end to these crossings, Lustig worked his scams in the United States, earning himself a reputation among law enforcement agencies as a smooth-talking and convincing conman. Never showy but always expensively dressed, Lustig presented himself as a man of quiet authority, upstanding and honest. So successful was Lustig that he even put together a Ten Commandments for Conmen that explained his methodology.

- Be a patient listener (it is this, not fast talking, that gets a con man his coups).

- Never look bored.

- Wait for the other person to reveal any political opinions, then agree with them.

- Let the other person reveal religious views, then have the same ones.

- Hint at sex talk, but don’t follow it up unless the other person shows a strong interest.

- Never discuss illness, unless some special concern is shown.

- Never pry into a person’s personal circumstances (they’ll tell you all eventually).

- Never boast – just let your importance be quietly obvious.

- Never be untidy.

- Never get drunk.

By 1925, he was in Paris and ready to pull off his most audacious con: selling the Eiffel Tower. The idea for the scam came from a French newspaper article about the expense of maintaining the Eiffel Tower in which the monument’s demolition was considered. The fact that this proposal was already being talked about gave credence to what would otherwise have been an outlandish proposition. With the plan forming in his mind, Lustig commisioned forgeries of government stationery and sent out invitations to scrap metal industry leaders, sparing no expense in his choice of meeting venue. The “sale” to Poisson had gone exactly to plan. With all the elements in place, why shouldn’t he repeat it one more time?

And so it was that just one month after his first Eiffel Tower con, Lustig once again was in the Hôtel Crillon in front of a group of potential buyers, giving them the same spiel as before. Only this time there was no “Poisson” in the room. One of the scrap metal dealers was suspicious and alerted the police after the pitch. Lustig fled to the United States.

For the next 10 years Lustig continued his scams and counterfeiting schemes across the States. One particularly successful one involved a mechanical box that he claimed could print banknotes (spoiler: it couldn’t). Another con was so convincing that master-criminal Al Capone fell victim to it. The law eventually caught up with Victor Lustig and in 1935 he was found guilty of counterfeiting and sentenced to 15 years in Alcatraz prison. He died in prison in 1947. The Eiffel Tower attracts 7 million visitors a year; the French government has no immediate plans to sell.

Al McKinnon, Calgary Canada

Thank you again, Jackie – once again, informative and entertaining. All the best … Al from Calgary Canada

Charis Wolf-Leyne

Really interesting article thanks!

admin

Thanks Charis! 🙂